A guest essay from Paul Newnes of LastExit, an international digital strategy, marketing, and design firm.

Considering the sophistication of humans as mammals, it is still interesting how we are doomed to repeat the same behavioral patterns.

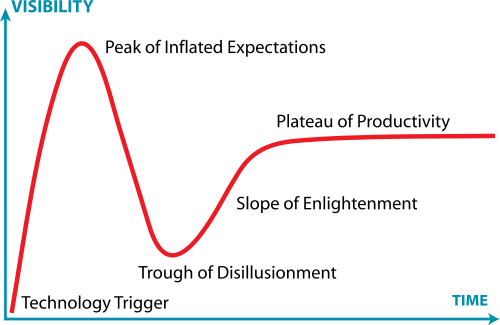

Gartner, the IT research consultancy, has made a considerable business around describing this, specific to technology. Their model is known as the Hype Cycle and shows the key change points, to no particular scale, of people’s attitudes to new technologies. Where a technology lies on the Hype Cycle has implications as to the level of investment a company might make in it.

The points as shown in the chart below are fairly self explanatory, but essentially illustrate that a mad dash towards a technology causes an inflated notion of what it can deliver; an opposite reaction caused by the realization that the technology isn’t a panacea and a lot of time/money/effort has been invested for little return; and finally, a growing sensibility towards a technology’s value-based application.

The key words here, of course, are “to no particular scale.” As with property prices and the stock market, we all have a sense that we are in a bubble or a trough; but calling the moments of inflexion is an art, not a science. The Economist, not usually known for its alarmist journalism, warned of the housing bubble as long ago as 2002, and in 2003 their economics editor Pam Woodall reported that “In many countries the stock market bubble has been replaced by a property-price bubble. Sooner or later it will burst.” As we are all brutally aware, Pam was right; some five years later it did, and spectacularly so.

There is a fairly easy translation of this model to social media. The recent Skittles/Twitter debacle shows a rush towards a technological medium with little thought as to the utility or value delivered to the end consumer. In fact one might consider that given the campaign was so open to abuse the value delivered was firmly in the negative territory and thus in the ‘Trough of Disillusionment.’

But how flawed is this approach? If a technology is at ‘the peak of inflated expectations,’ then is it fair to assume that the end-consumer has comparably inflated expectations? If so, then is the net sum zero?

This would seem a tremendously dangerous position to take. It is a fair assumption to make that the consumer’s attitude towards social media has a quotient of hype, perhaps even equivalent to that of the brand or agency. But the disenchantment that will be felt after by the consumer has a direct impact upon the brand’s equity. This may well track with the overall disenchantment trend of the new medium, but will be more or less guaranteed not to outperform.

The irony is that mediocrity may involve having greater visibility than a sensible, utility/value driven social media campaign. Indeed, when one considers demography, this irony falls into even sharper focus. A number of organizations have analyzed Twitter’s users including Compete, Hitwise, Quantcast, Nielsen and Twitterholic. Two statistics stand out.

Firstly, as of August 2008, California residents accounted for more than 57% of Twitter’s visitors.* If that doesn’t raise the eyebrow of the marketing executive busy planning a Twitter campaign in Europe then nothing will.

Secondly, none of the analysts can agree on which age group the lion’s share of users belongs to. Neilsen and Hitwise believe 35–49 year olds dominate (41.7% of users at February 2009, Hitwise); Quantcast says 47% of users are between 18 and 34. And when it comes to gender Quantcast states that 53% of users are female(March 2009) which is quite a shift (if true) from Hitwise’s analysis in August 2008: 63% male.

Buzz is rarely an undesirable commodity, but given the increasing need (and increasingly possible ability) to target marketing activity where it will be most effective, this vagueness is unlikely to guarantee a successful campaign. And whichever way you slice the numbers there are large chunks of people missing. Those that are present may have zero chance of becoming customers; and although people engaging with your brand can have value – because they can tell others who could be – in lean times they don’t add up to a can of beans.

So, compare and contrast the release of new Ford car models in the US and Europe. A relatively simple but well structured exercise in user generated content, versus Skittles. In the short run Skittles had far greater visibility but over the medium to long run will be recognized as a less than mediocre campaign.

In this instance it would seem the brains behind Skittles went purely for visibility, rode the peak and then fell squarely into the trough. Ford, however, “has learnt about using different ways of connecting with consumers, playing the long game” with its ‘This is Now’ art-focused UGC initiative, according to a blogger on bizzia.com.

But how long is the long game? A lot shorter than it was five years ago. In those five years it has taken for The Economist’s predicted house price bubble to burst, Facebook has launched, attracted 200 million users and earned valuations in excess of $5 billion. In those same five years IBM, inventor of the PC, stopped making personal computers. Last week, Silicon Graphics filed for bankruptcy.

So, although on one hand you can understand the desire to jump on any bandwagon that rolls along (and many will salute the bravery of Skittles social media endeavor), it is worth remembering that not all will succeed, and even those that seem to be enjoying a meteoric and unstoppable rise may not be all they are cracked up to be. The tortoise won the race, remember.

The moral of the Hype Cycle? If you even suspect a technological medium is at the peak of inflated expectations, go for a pure visibility campaign at your peril. And if you know of a sure-fire way to predict the peak, let me know.

* Bill Tancer from Hitwise, Time Magazine